Mitigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Small Businesses By Improving Indoor Air

As the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic worsened on the West Coast and in the Northeast, businesses in economic epicenters such as Los Angeles and New York went into a tenuous shutdown mode. Some organizations were deemed essential and had to stay open, while others could continue operations if adjustments were made. Many businesses, particularly small businesses, were either not on the essential list or couldn’t make the necessary changes to their physical or operational structure to stay open. The impact of the pandemic will continue to be most strongly felt by these small businesses. In reopening, they must make mandated adjustments to ensure the safety of their staff and customers, but also to try to avoid another period of lost business—the economic impact of which many cannot survive. As the pandemic has stretched on through three quarters of the year, much has been learned about how it is transmitted, where it is most likely to be so, and what steps can be taken to reduce the potential spread. With the greatest transmission source being through inhalation of airborne particles, it is central to businesses to control the air quality within their facility. There is much that can be done in this area to safeguard both people and businesses’ ledgers moving forward.

Small Businesses Concerned About Closing Again

Nearly 59 million people in the U.S. work in small businesses, those defined as having fewer than 500 workers. This represents more than 47 percent of the country’s total workforce. Annually, 1.5 million more jobs are created by these businesses, which is 64 percent of all new jobs created in the U.S.

With reopening at various stages across the country, a U.S. Chamber of Commerce poll conducted in June 2020 found “Most small businesses report being at least partially open…79 percent of small businesses are either: fully (41%) or partially (38%) open.”

The Chamber notes, “Looking ahead, 66 percent are concerned about having to stay closed, or closing again, if there is a second wave of COVID-19. More are anxious about this in the West (77%) and Northeast (74%) than in other regions.”

The survey found that most small businesses were either planning to make changes or had already begun to do so. Most were focusing on frequent cleaning and disinfecting, employee policies such as self-monitoring and encouraging them to stay home if sick, use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and social distancing.

“As small businesses adapt to the new environment, three in 10 anticipate needing more guidelines on how to keep customers and employees safe and well,” according to the Chamber. “Around one in five expect needing more guidance from political leaders on how to respond, more resources for understanding the outbreak, and guidance on healthcare, insurance, or accounting issues.”

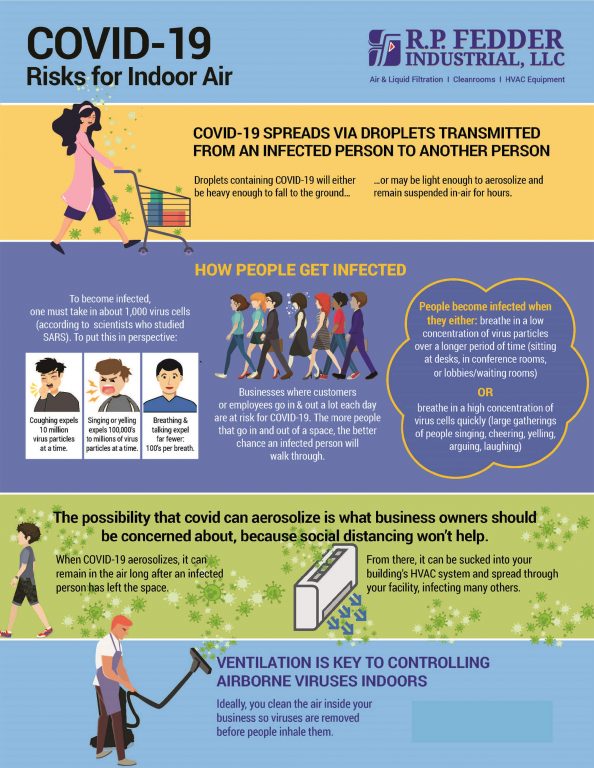

Primary Means of Transmission of COVID-19

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), person-to-person transmission of the virus that causes COVID-19 occurs primarily when someone inhales respiratory droplets produced by an infected person. This is particularly the case when the droplets have become aerosolized and are easier to inhale into the lungs. While coughing and sneezing are obviously problematic, so too are yelling, singing, cheering and even talking and breathing, all of which expel infected droplets into surrounding air. Much of the virus matter exhaled by an infected person is on particles that will fall to the ground within a radius of six feet. However, virus matter that doesn’t fall to the ground could linger in the air as an aerosol or attach to dust particles, which then get recirculated throughout the space. Extended exposure time to a low concentration of infected airborne droplets is just as problematic as a short-term exposure to a high concentration. One study in the New England Journal of Medicine suggested COVID-19 can live in the air as long as three hours in the right conditions. These conditions include indoor spaces that either have large numbers of people in them at one time (event spaces, gyms, malls, etc.), many people passing through so droplets may linger in the air (lobbies and entryways, waiting rooms), and those with poor ventilation and air circulation (older buildings or those with older HVAC systems). That means occupants spending extended time within an indoor space can be at risk even with social distancing and/or long after an infected person has left the premises.

Additionally, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in late March found that droplets that were produced when someone coughs or sneezes can travel up to 27 feet. The study was not conducted specifically on the COVID-19 virus and there are many factors that impact how droplets survive and fall. However, the study does demonstrate the wide variation in how far droplets can travel and the need to be aware that the social distancing standard of six feet may not always be sufficient.

Transmission Thrives Indoors, In Crowds & With Poor Ventilation

In a May 2020 interview in The New Yorker, Asaf Bitton, a primary-care physician and public- health researcher who directs the Ariadne Labs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard’s School of Public Health, discussed what he sees as higher-risk situations and locations. “I think that what we’ve learned by understanding some of these super-spreading events, but also by carefully monitoring what’s happened to our health-care-worker population, is that … The majority of transmission is happening in indoor, poorly ventilated environments commonly used by multiple people who are coming in and out. And I think that’s where the focus of our transmission reduction should be.”

The activities that take place within the space also have significant impact on risk. Activities such as singing and yelling expel more droplets than are transmitted through breathing and talking. Health experts became concerned about this type of activity-based aerosol transmission after dozens of choir members contracted the virus following a 60-member, in-person practice in Mount Vernon, Washington. In a study subsequently published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,” researchers emphasized that “the act of singing, itself,” might have contributed to transmission. This was thought to be because the more robust act of singing and projecting the voice expelled more virus, but also because some people—known as “superemitters”— release more particles into the air when they speak by being “unusually loud or slobbery.”

Two of the earlier super-spreader indoor events took place in February. According to an article in “The Atlantic,” on February 16, “a 61-year-old Korean woman with COVID-19 triggered hundreds of infections when she prayed with 1,000 worshippers in a large windowless church in Daegu, South Korea. (To this day, more than 60 percent of Korea’s COVID-19 cases are in Daegu.) Two days later, in France, several hundred Christian worshippers from around the world packed into a dark auditorium in the small town of Mulhouse for an annual festival. French authorities have since linked more than 2,000 global cases to this one meeting, including cases in French Guyana, Corsica, Burkina Faso, and Switzerland.”

Possibility of Viral Spread Over Air Systems

Following these super-spreading events, healthcare experts advised reducing gatherings of large crowds indoors, particularly in poorly- ventilated spaces. However, there have also been many studies focused on the potential for virus particles to spread through a building’s heating, ventilation and air conditioning system.

A recent article in “Air Conditioning, Heating & Refrigeration News” addressed this potential. In the article, Professor of Architectural Engineering at the Pennsylvania State University and founding director of its Indoor Environment Center, William Bahnfleth, Ph.D. explained, “If I were to cough or sneeze in your direction unprotected, some of the virus-containing droplets coming out of my mouth or nose might enter your mouth, eyes, or nose and cause an infection.” He went on, “But there’s also the potential for airborne transmission. And if viruses that are viable are in those droplets that you’re producing, some of them will be small enough that they will stay airborne for a long time. So, it’s not impossible that infectious particles in the air could stay aloft long enough to be collected, say at the return grille of an HVAC system, go through a duct, and infect someone in a different space.”

Similarly, Ed Nardell an infectious disease expert at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health discussed the potential for particles to remain airborne and cause infection during an interview on WGBH, Boston’s NPR affiliate: “Now they’re falling, falling, falling, and some will hit the ground and they won’t evaporate anymore. They’re settled,” he said. “But others, before they hit the ground, start to evaporate. And pretty soon, they are airborne. And those can float on air currents indefinitely unless they’re vented out or inhaled.”

Perhaps the most significant anecdotal evidence for the ability of virus particles to be transmitted via indoor air systems is an event that took place in China in January. The CDC published initial study findings of an outbreak linked to the airflow in a Guangzhou, China, restaurant. Over the course of 12 days, nine people who ate on the same level of a multi- level restaurant developed COVID-19. It was determined that all infections were linked to one patient with a COVID-19 infection, and that the only people to contract the virus were those at tables in direct airflow of the restaurant’s air conditioner (and downstream from the infected person).

Reasons to Take Action in the Workplace

Reduce economic loss from employee illness

As the ability of a small business to operate relies heavily on keeping its workforce on the job, it cannot be understated how important it is for businesses to implement virus-prevention safeguards. Consider COVID-19 can last from two to as many as 10 weeks in severe cases and infected employees will be out of work for its duration, and those who have come in contact with them are unable to return to work for at least 14 days. The potential impact of sick-pay and lost productivity for any one company is significant. In exceedingly small companies that cannot switch the burden of work from one missing worker onto others, having someone out for weeks can be devastating.

In April, the Integrated Benefits Institute (IBI) shared research findings in which they anticipated that lost time from work caused by COVID-19 could cost employers more than $23 billion in employee benefits for absent workers. The study indicated “Up to 5.6 million employees could be impacted during the pandemic if efforts to curb the spread prove insignificant, with almost three million workers at firms with fewer than 500 employees entitled to paid leave per the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) that went into effect on April 1, 2020.”

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, “The risks from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), for workers depends on how extensively the virus spreads between people; the severity of resulting illness; pre-existing medical conditions workers may have; and the medical or other measures available to control the impact of the virus and the relative success of these measures.”

The National Institutes of Health found that “Nearly 80 percent of all workers have at least one health risk and 11 percent are over the age of 60, with an additional health risk.” The Institutes noted that, “Even when obesity, the most common health factor, was excluded from studies, 56 percent of the workforce is at risk and 10 percent are over 60 and at risk.” The NIH also noted 11 percent of workers in essential industries do not have health insurance. This could lead to a reluctance to seek timely treatment, which clearly exacerbates the risk of complications and potential to transmit the disease to coworkers and customers.

Defend against charges of not doing enough

Beyond the direct impact of an employee contracting COVID-19, businesses are concerned about liability and lawsuits. According to the same U.S. Chamber of Commerce poll conducted in June, two-thirds of small businesses with 20-500 employees were significantly less concerned, but still one-fifth were worried.

“Manufacturers (43%) and retailers (40%) are most likely to express worry about lawsuits, with less in professional services (33%) and services (30%) sharing the sentiment,” according to the Chamber.

Additionally, numerous articles have been written by legal experts regarding employees refusing to return to work out of safety concerns amidst the COVID-19 crisis. An article by law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck notes, “Employees with reasonable safety concerns—for instance, where they assert that the employer is not taking reasonable steps to provide a safe workplace—also may be protected under the Occupational Safety and Health Act and, if they are acting not just on their own behalf, under the National Labor Relations Act. Failing to act appropriate with respect to such employees may lead to whistleblower complaints, among other things. Collective bargaining agreements should also be taken into account, where applicable.”

Establish trust with employees and customers

A business needs its employees to be healthy and on-the-job, and it also needs its consumers to return with their loyalty and their wallets. As states have remained open or reopened their economies across the country, it’s become obvious that just hanging an “Open” sign on the door may not be enough.

In a July 18, 2020 survey reported by McKinsey & Company, “Consumers are actively looking for safety measures when deciding where to shop in-store, such as enhanced cleaning, masks, and barriers. One-fourth of consumers believe that a company’s treatment of its employees has increased in importance as a buying criterion since the crisis started. Companies’ actions in this time, especially toward their consumers and employees, will be remembered for a long time and can lead to goodwill.”

The company noted that “70% of consumers are not comfortable going back to ‘regular’ out-of-home activities. Most consumers are waiting for milestones beyond governments lifting restrictions—they are waiting for medical authorities to voice their approval, safety measures to be put in place, and a vaccine and/or treatment to be developed.”

Physician Bitton shared in “The New Yorker” article, “What I have told my friends in the business and economic communities is that you need trust in order to reopen your economy. And just because you reopen your business doesn’t mean that it’s there. You can’t declare trust by fiat. You have to build it. People have to have the sense that going to your place of business, resuming their daily life, will not entail an undue, overwhelming risk for them or their families.”

Strategies for Reducing Virus Transmission in Your Workplace

Penn State’s Bahnfleth also chairs the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air- Conditioning Engineers’ (ASHRAE) epidemic task force, which has been providing written guidance for building managers and those in the HVAC industry. In a July 21 interview on WGBH, Boston’s NPR affiliate, he indicated the key to protecting different types of businesses from risk is to reduce the concentration of potentially infected particles in the air.

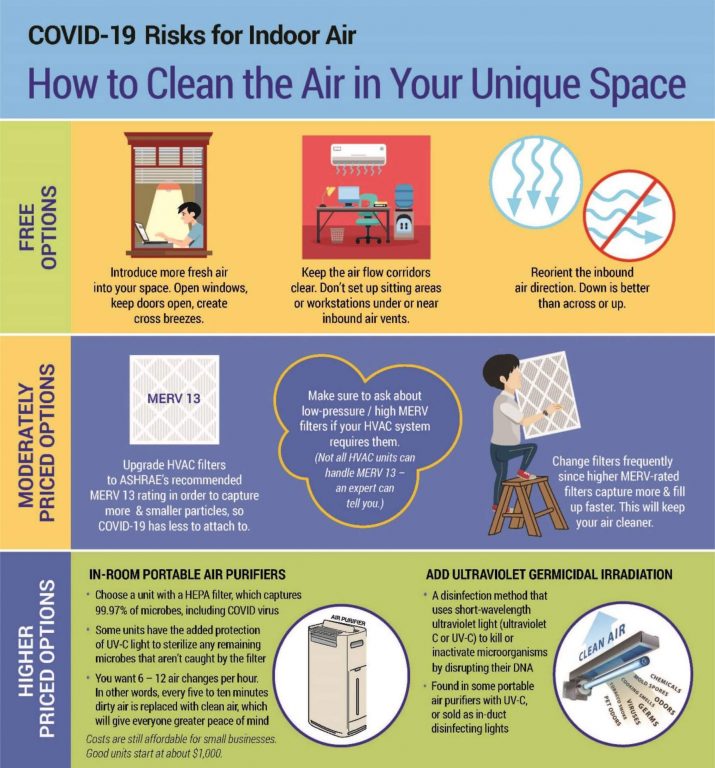

“One of the best ways to do that is simply to bring in a lot more outside air into a building, because that outside air replaces indoor air that may be contaminated, and that lowers the concentration,” he said.

R.P. Fedder Industrial, LLC, a filtration solutions company serving Central and Western New York, also has been busy advising companies on how to improve their indoor air quality since New York began phased reopening in May. The company has developed customized filtration and air quality solutions for companies across a variety of industries, including healthcare and education, for 60 years. It is now bringing its expertise to bear to help businesses reduce the potential of virus transmission indoors.

Agreeing with Bahnfleth, the company’s President, Chris Fox says, “There are a lot of things companies can do just to create better air. One of the first things that can be done most anyplace is open the windows, introduce more fresh air and not recirculate the air as much. Just the introduction of fresh air will reduce the amount of concentration of virus- infected particles in the air.”

Of note, the CDC, in their “Guidelines for Business,” also recommend companies consider increasing ventilation rates and/or increasing the percentage of outdoor air that circulates into the building ventilation system.

Another important but simple and economical tactic, Fox advises, is to keep the airflow corridors clear. “Make sure you don’t have sitting places or workstations in close proximity to the inbound air vents or directly in the path of fresh air inflow from windows or doors,” he says. “And if you can reorient the HVAC system’s inbound air direction so it’s down toward the floor rather than across or up, less air (and potentially particles) will flow directly in front of or across people.”

Improving the Air You Control

In many cases it will not be possible to simply open windows; in many modern buildings windows aren’t even designed to open. Cold weather will arrive (in many parts of the country) in the height of cold and flu season and what is now expected to be the most dangerous portion of the COVID-19 timeline. Bringing fresh air directly into a workspace will prove to be too uncomfortable and impractical.

“It’s important to look at air quality as a multi- faceted system,” says Fox. While fresh air is a free and simple addition, most businesses will have to rely on an environmental control system and that will be where a key portion of strategy should be focused.”

Among the more inexpensive solutions Fox recommends is to upgrade the filters in the HVAC system to capture more particles and smaller particles. “If the virus’ small droplets can attach themselves to dust particles and those dust particles can move through the room and the air system, filter out those dust particles so there are fewer of them for the virus to attach to,” he advises. “Better air filtration in these heating and air conditioning systems will absolutely reduce the risk of transmission.”

Not all filters capture particles equally; the filter’s efficiency is critical in determining its ability to capture the size of particles that contain viruses. (“Efficiency” refers to how much particulate of various sizes is captured by the filters.) ASHRAE has set a filter rating scale – referred to as Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) ratings—where a higher MERV number equates to a greater percentage of ever smaller particles captured by the filter. The organization recommends MERV 13, or as high as the HVAC system can handle, as the most effective in capturing the virus that causes COVID-19.

To remove virus matter from the air, an air handling system pulls air from the room, moves the air through a high MERV filter, and puts the filtered air back in the room. The air circulates through the system typically two to four times an hour, or once every 15-30 minutes.

While it may seem, then, that a building manager just needs to put in a higher MERV filter, it is not that simple. One challenge is that the MERV rating of a filter may deteriorate with time, sometimes deteriorating to MERV 8 in a matter of just a few weeks. “Many filters weren’t designed with life-saving functionality in mind, so declining MERV ratings didn’t matter. Now it matters because that filter is supposed to be capturing COVID-19 infected particulate,” says Fox. All filters sold in the United States must be tested per ASHRAE standards, and that test includes evaluating performance over the life of the filter. Fox recommends building managers look at a filter’s MERV-A rating, which more accurately represents the filter’s true efficiency over the life of the filter.

Another challenge for building managers is that higher MERV filters reduce air flow, resulting in the air handling system working harder to pull the air through, which means more energy consumed. Fox points out, “Our energy consumption models, which we have validated in real-life environments, show that building owners can expect to see their electric bills increase $30 to $50 per filter per year, and more if they don’t change them frequently. Given the number of filters in a typical commercial building, that easily means thousands if not tens of thousands of dollars per year.”

There are ways to design a filter that will meet the higher-MERV rating and keep the energy bill down. While that increases the initial cost of the filter, it is more economical in the long run.

Where installation of MERV filters is not practical, installing UVC into HVAC ducts is particularly useful as UVC sterilizes the air.

This practice has been used by hospitals for years and is now being deployed in commercial and industrial sites.

According to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (a U.S. Department of Energy National Laboratory Managed by the University of California), “Ultraviolet (UV) germicidal lights produce short wavelength light (or radiation) that can damage the genetic material in the nucleus of cells of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and molds. The cells may be killed or made unable to reproduce. With extended exposure, UV germicidal irradiation (UVGI) can also break down the particles that have deposited on an irradiated surface.”

Additionally, the nonprofit International Ultraviolet Association (IUVA), has stated UV is a known disinfectant for air, water and surfaces that can help mitigate the risk of acquiring an infection in contact with the COVID-19 virus, when applied correctly. “The IUVA has assembled leading experts from around the world to develop guidance on the effective use of UV technology, as a disinfection measure, to help reduce the transmission of COVID-19 virus,” says Dr. Ron Hofmann, professor at the University of Toronto, and president of the IUVA.

By installing UVGI systems in the ducts of HVAC systems, the UV light irradiates small airborne particles, which may contain virus particles, as the air flows through the ducts.

Special Situations and Tricky Spaces

Lastly, there are situations where common sense suggests changing the air every 15 to 30 minutes just isn’t frequent enough given the use of space. For example, the air in a hospital operating room changes over and gets filtered every five to six minutes through HEPA filters.

Recent viral filtration efficiency testing conducted by LMS Technologies found the HEPA filtration media manufactured by R.P. Fedder remove 99.999 percent of viruses from the airstream. (The test challenged the R.P. Fedder HEPA Filtration Systems used in XLERATOR® Hand Dryers with approximately 380 million viruses ranging in size between 16.5 and 604.3 nanometers.)

“To be certified as HEPA, 99.97 percent of particles larger than 0.3 microns must be captured by the filter,” explains Fox. The company has its own testing facilities to measure both efficiency (i.e., a particle counter) and pressure drop of every filter it manufactures. “We can measure the actual efficiency of capturing these small particles, and therefore the filters’ compliance with HEPA requirements. This is critical at this time when organizations are looking to every means possible to reduce spread of COVID-19 and other viruses.”

There also are spaces within buildings where owners and managers might want to consider having an extra layer of protection to better protect their customers, employees and themselves. Examples include spaces where:

- Many different people pass through or congregate for an extended period of time, such as lobbies, conference rooms, dining areas, and other common areas.

- People expel more air from deeper in their lungs, such as from cheering or singing or heavy exertion.

- Occupants need protections, such as in long term care facilities or critical service.

In these situations, in-room, portable, HEPA air purifiers can filter and clean the air more rapidly and independently of the air handling system. Many come with UV-C lighting internal to the purifier which, as noted earlier, sterilizes any microbials that manage to get through the filters.

Benefits/attributes of in-room air purifiers:

- HEPA filters capture 99.9%+ of microbes, including COVID virus, with the option of added UV-C protection to sterilize any remaining microbes that aren’t captured by the HEPA filters.

- With portable units, one can typically see six to 12 air changes an hour, or once every five to 10 minutes.

- Costs are affordable for small businesses – good units are about $1,000, or about $5 a square foot.

R.P. Fedder has recently sold more than 200 units of the V-PACTM SC Self-Contained Air Purification System to customers in the health care industry in Upstate New York. This portable unit features HEPA filtration plus UV. This combination is recommended by ASHRAE, and destroys viruses, bacteria and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

Demand for air purifiers, especially those with UV-C, has now outstripped supply, and Fox warns the situation will only get worse. “The backlog for these devices is now six weeks, and growing longer,” he adds. “Inquiries are coming in from schools, offices, restaurants, salons, dental and medical practices, most any place where people remain in a single place for an extended time.”

Fox expects that, even where not required, supplemental room air purifiers with UV-C will become the norm in many consumer businesses and offices. “People will take comfort in knowing that the air around them is safe, having been recently cleaned and sterilized,” he says. “They don’t want to have to be concerned with who might have been through the space previously or worry that someone on the other side of the office or restaurant or whatever might be contagious.”

Conclusion

Few small businesses in the United States – or likely the World—were prepared for the impact of a global pandemic. While some managed to adopt a new operating model within a short time frame (creating take-out and drive-up options, switching from distilling liquor to hand sanitizer, etc.), others suffered serious, long-term setbacks. All businesses that survived the first stage of the pandemic must now adopt strategies to avoid additional lost productivity and revenue from viruses, whether seasonal flu or that which causes COVID-19. It is imperative that improving indoor air quality becomes part of an overall approach to reducing potential transmission of the virus. There are vast enough technologies and strategies available that small businesses can find an approach that works for their space, operational model and budget.